The Summer Of Rave 1989 (Full Documentary HQ)

Download information and video details for The Summer Of Rave 1989 (Full Documentary HQ)

Uploader:

robotsistromPublished at:

8/27/2013Views:

1MDescription:

Documentary by the BBC on the development of rave culture in the United Kingdom during the summer of 1989.

Video Transcription

Great British summers.

They may not come often, but when they do, people across the nation start shedding not only their clothes, but their inhibitions too.

That summer is an amazing experience.

It's an amazing year.

It's a time to challenge convention, cast out the old and bring in the new.

And if summertime is party time, the scorching summer of 1989 was one long party from beginning to end.

Young people were turning their backs on the rat race and throwing themselves into a hedonistic rush of new music and new drugs.

Acid House was as big as punk.

It was as big a youth explosion as has ever taken place in this country.

We are going to change the world.

We're going to make everyone happy people.

We're going to make everyone like us.

The atmosphere was amazing.

The way everybody came together was amazing.

And you just felt like your generation had found its expression.

And all around the world, other people were finding theirs.

From pro-democracy movements in China to breaking down borders in Eastern Europe.

I am free!

Britain's homegrown youth revolution sent shivers up the spine of Middle England.

One of the things I remember as Home Secretary, particularly in the early days, was being told that a long heatwave meant trouble.

1989 saw the hottest, sunniest and driest May for 300 years.

A lot of dry weather around, a lot of sunshine.

Certainly a very warm afternoon just about everywhere, 28 in places.

Temperatures at least as high as today, if not a degree higher.

It was so hot the flowers were wilting at the Chelsea Flower Show.

The old hands have never known a year like it.

Phew, what a scorcher.

But the warm weather wasn't the only thing to celebrate.

Mrs Thatcher was celebrating her 10th year in power, and thanks to her policies, a lot of people had made a lot of money.

I look back on the summer of 1989, and really what I see is a vista of money.

There was masses of it, and it all kind of ran around in braces and stripy shirts, and they were yuppies.

What sort of a car have you got?

I've got a BMW.

Being seriously rich is seen as being a very interesting and clever occupation.

It seemed as if Britain in the 80s had embraced a new set of values.

the once powerful trade unions had been tamed.

Now, survival of the fittest was the order of the day.

We suddenly became individuals and it no longer mattered what background we came from.

If you had it within you and you were ambitious, you could get on and make your life.

By the summer of 89, an entire generation of young people had grown up under Tory rule.

Thatcher's children were encouraged to value individual prosperity above all else.

It's more socially acceptable to be selfish, to say, I want money, I want a house, I want a car, to have all these things.

It's far more socially acceptable to be greedy.

It was a time when what kind of job you could get, what kind of career you could follow, how you could make money seemed to be most important.

There was a pretty widespread feeling of political apathy, perhaps not just amongst the young people, but particularly amongst younger people.

It felt like nothing was ever going to change.

We had the Iron Lady in charge, the lady who was not for turning, who was never going to change her mind about anything.

We had three general elections in which she won by landslides.

And there was a real sense that this is what life is now, just get used to it.

But not everyone had a stake in this economic miracle.

And while the rich were getting richer, the poor were worse off.

For many, Thatcherism had a hollow ring.

Around that time, we had Mrs. Thatcher saying there's no such thing as society.

And it did seem to be that out there in the kind of big, wide political world, it was every man for himself.

And there was a kind of breakdown, really, in people taking kind of responsibility for each other or kind of feeling that we were all in it together.

So this is how it feels to be lonely This is how it feels to be small

Britain was a very grey, grim place.

You know, I mean, now we think of people making lots of money in the city and sort of cocktails, Club Tropicana atmosphere, but that was very much a small elite of people in central London.

Elsewhere, there wasn't a lot to do.

There were an awful lot of restrictions.

You felt boxed in.

But by the summer of 89, young people were beginning to break free of these constraints.

A new underground dancing, Acid House, was turning from a low-level rumble in the capital into a youth movement on a massive national scale.

You'd be out till 9 o'clock in the morning and feeling like you were part of something different.

You were part of this secret movement that, you know, overground, the normal man in the street didn't know what he was up to.

The scene was defined by a new look, a new drug, and a new sound, house music.

At 120 beats per minute, it was the perfect dance track.

It wasn't hard to dance to Acid House.

All you had to do was wave your hands in the air and jump up and down, so suddenly everybody could have a go.

It was the first time I realised white people could actually dance.

Do you know what I mean?

Because there was this thing that white people couldn't dance.

It had a real trance-like element to it.

And I think it was that sort of extra dimension that you got into.

You went somewhere else in your head.

People did believe that their consciousness was being expanded.

Helping ravers achieve this altered state was a drug which seemed perfectly suited to the new dance culture.

Enjoy this trip.

And it is a trip.

Ecstasy was a widely available, easy-to-pop little white pill.

I think that a lot of different scenes come hand in hand with certain drugs, especially when you're talking about music.

And as sad as that may seem, it's just fact.

Ecstasy, without a doubt, was the drug of choice, the way that it kind of made people throw away their inhibitions, the loved-up-ness.

Well, I think one of the key things about ecstasy is it was very difficult to drink alcohol once you'd had a pill because you got dehydrated, so you drank water.

So there was no one getting drunk.

There was no one getting aggressive.

So that was what it wasn't.

And what it did do was it gave you a whole sense of openness and of love.

While everybody was on a...

Everybody was in this hugely empathic state, and if you were at a party with 20,000 people all on the same drug, it was incredible, but you could go to that party and not be on that drug and still feel that feeling.

This sense of togetherness had a particular attraction for young people feeling isolated by the Thatcherite values of the 80s.

I always think that youth cultures in some way go the opposite way from the prevailing cultural mode, political cultural mode.

At a time when we're all individualist, and, you know, Thatcher's created the modern Essex man with his mobile phone and his greed, that a sense of unity and community was going to be the obvious antipathy to that, and that came with this incredibly communal drug.

Like youth movements before it, the rave scene came with its own uniform.

It was all about baggy.

It was all about fluoro.

Really, really bad taste clothes.

We're talking the late 80s here.

Dungarees.

Oh, my God.

So unladylike.

I don't know what we were thinking, but the baggier the better, the bigger the better, the more freedom the better, I guess.

When you looked out from the stage, you could just see this sea of colour.

Purple and green and all these rainbow colours, man.

So that was a part of that feeling special.

The uniform, you know, was part of the movement, man.

Together with the great music has to be a certain clothing look, a drug, part of the small people.

And certainly, Acid House had that as strongly as punk had had it before.

Challenging the values of society wasn't purely a British phenomenon that summer.

All over Eastern Europe, a peaceful revolution was taking place which would have profound global consequences.

Millions were rejecting communism and taking their first steps towards democracy.

All the news coming through the door was good news, amazing news.

It was the crack-up of the Soviet Empire.

It was what we used to call the satellites in Eastern Europe shaking themselves free in different countries in different ways.

These were amazing things.

And we didn't realize, perhaps soon enough, how complete that crumbling away was going to be.

Inspired by the pro-democracy movements in Eastern Europe, hundreds of thousands of Chinese students staged a peaceful sit-in in Tiananmen Square.

Remarkably, the Chinese authorities stood by, unsure at first how to respond.

As the established world order of half a century was crumbling, at home, another era was coming to an end.

The once invincible Mrs. Thatcher seemed to be losing touch with reality.

We have become a grandmother of a grandson called Michael.

If the ground could have swallowed me up when I'd heard she'd said, we are a grandmother, I wish it had.

It was very embarrassing.

She had never been more regal, she had never been more presidential, and she swung around as though the world was at her feet, and in many ways the world was at her feet.

But beneath that, she was actually losing grip of the detail of things, losing grip with the direction of Thatcherism.

But even if the Iron Lady's vice-like hold was weakening, the impact of Thatcherism on British culture was total.

Profit-seeking private enterprise was king.

Record producers Stock Aitken and Waterman were an embodiment of the economic miracle.

Their manufactured, mass-produced music sold millions.

In 89 the media put us down as the respectable face of Thatcherism.

You put one of our songs, the minute it went on top of the Pops, boo, the next week we were number one.

Because we opened it out to that big family audience.

And of course, the great thing about 89, which everybody remembers, and we certainly played on it, was fabulous weather.

Jason Donovan coming up that hill with his guitar, mate, and the sun was shining, and boo, you didn't have to be in Australia, you could be in Tipton, it was fantastic.

Blonde-haired heartthrob Jason Donovan was the biggest selling artist of 1989.

What I did was capture people's hearts and imaginations and those memories stick with you, you know, for the rest of your life.

I know because the records I used to listen to in those days mean so much to me today.

Jason Mania swept the country.

During his tour, it was reported that teenage fans were fainting at a rate of one every 12 seconds.

I think the fainting numbers were exaggerated.

It made good copy.

It made me think, wow, God, I do have an effect.

Maybe I should go into religion.

Welcome, Jason and Kylie, back to going live.

How can you leave us like that?

Stock, Aitken and Waterman were masters at marketing their records to a teenage audience.

Though in Jason and fellow Aussie Kylie Minogue, much of the job was already done.

Neighbours

By the summer of 89, the unthreatening soap opera world of Ramsey Street was drawing in audiences of 13 million.

G'day.

How's it going?

Good day at the workshop?

I thought you'd be in the library.

Yeah, we were going to go to the library.

Because of Neighbours, we were part of a culture rather than just a pop hit.

People knew us, or they thought they knew us.

You're a genius, Scott.

Why Kylie was the most phenomenal artist, probably for the last 20 years, is because girls all associated themselves with her.

You know, she was the perfect kid next door.

She was, you know, she took the spanner out and fixed the car.

And she got this hunk of a boy friend called Jason.

Come on.

Can't get a better story than that, can you?

Even stars plucked from obscurity were made to fit the formula with a carefully designed image.

I used to look quite old when I was 17, because I used to have really long hair right down to my waist.

I used to wear a lot of leather.

I was kind of like a rocky type of chick.

But of course, Pete didn't want that type of image.

He wanted me to look younger.

So I was quite devastated when they cut and permed my hair.

In fact, it was mortified.

I think that's the way Pete liked it.

He liked us all to be nice and clean cut.

We wanted the perfect idols that the kids could look up to.

Branding stars wasn't just about selling records.

Pop supported a whole sub-industry of related products.

Magazine Smash Hits was the handbook for pre-teen consumers and the perfect way for advertisers to reach the new pocket money market.

1989 was a recognition in the power of the teenager in terms of spending power and influence on society.

The youth audience was a valuable audience and it was the time to start.

building your brand awareness to somebody who's 11, not waiting till they're 21.

So a bank like Midland would target an 11-year-old in the belief that you'd continue having a Midland bank account at 25, 30, 40.

So they were spending millions of pounds on the youth audience at that time.

But not everything happening in popular culture was quite so packaged and profit-led.

In Manchester, a homegrown version of acid house culture was attracting nationwide fame.

The city that had given the world the Smiths and New Order was by the summer of 89 fizzing with new energy and musical creativity.

Everything centered on one drafty nightclub called the Hacienda.

This is the Hacienda.

It may not look much, but it is the cathedral to host music in Britain.

This is the gateway to the dance floor.

Everybody, even the bar staff at the back of the bar, would be moving, would be moving to this beat.

And I've never seen rhythm and movement saturate buildings and human beings the way that Acid House did.

It's never happened before or since.

More than just a nightclub, the Hacienda became the focal point of Manchester's cultural explosion.

Everything came out of a Hacienda.

Dance music came out of the Hacienda, bands came out of the Hacienda, and anybody who wanted to have any sort of sense or feeling of what was going on in that town was in the Hacienda.

The club spawned a new wave of bands that came to change the face of British pop music.

One band that defined the scene on the Hacienda's dance floor was Happy Mondays, fronted by Shawn Ryder.

Sean has taken more drugs than most human beings now exist, and in Manchester, that's a real man.

Even though they had the line-up of a traditional rock band, Happy Monday's music came straight out of the dance and drug culture.

Happy Mondays capture this sort of heady, intoxicated swirl.

It's all very disoriented.

It's like your head's spinning a little bit.

It's like you've had a bit too much eat.

They even had one member, Bez, whose sole function in the band was to dance.

It was perfect at the time for the Mondays, cos it was everything we were trying to do, and put across, like, this dance, off-beat dance music.

And what the ecstasy done, it's made everyone understand what we were trying to do, cos no-one quite understood us at first.

Another local band to emerge from the burgeoning dance scene would go on to cement Manchester's status as the centre of the musical universe.

The Stone Roses released their now legendary debut album in April.

The initial reviews may have been lukewarm, but the band had a swagger and a confidence about them from the start.

We knew the power of what we had for the songs and we knew we were going to be enormous.

And it's not arrogant to say that, it's just that's the self-belief that we had.

We knew we were going to be huge.

And we knew we were of the time, and the times were changing, and we were going to be the vanguard of kind of a new movement, or whatever it was.

And it was great to be part of it.

For a generation brought up on a diet of electronic pop, the Stone Roses' music was unfamiliar territory.

They have this kind of funk influence, this loping, syncopated beats and stuff like that, which is now so much part of the kind of landscape of music that it's difficult to understand how weird that sounded in, like, 1989.

While Manchester was enjoying a cultural explosion, their neighbours in Liverpool were basking in summer sporting success.

The 1989 FA Cup final was a Merseyside derby.

With the scores leveled deep into extra time, it was a nail-biter.

McMahon, Barnes.

Rush, goal!

3-2 Liverpool.

Ian Rush gets his second.

And this now becomes one of the most dramatic FA Cup finals of recent times.

Liverpool's victory had a bittersweet quality to it.

A month earlier, the club had lost 95 of its fans, many very young, at the Hillsborough Stadium disaster.

Bad management of the crowds had led to the fatal crush.

The tragedy was too much to bear for fans of an already beleaguered game.

Throughout the 80s, football had been blighted by terrorist violence, a seemingly intractable problem.

Indeed, the tragedy at Hillsborough might have been averted had the police not assumed they were dealing with crowd trouble.

Terrorist violence was a real problem.

This was a period of really rather frightening...

which needed legislation, but drafting that, getting that right, getting the clubs to agree to it, getting it through the House of Commons, was one of the most difficult technical, political things that we had to do, and it was very important.

Despite the best efforts of the police and government, the hooligans had not gone away.

Bizarrely, the solution to this scourge of society lay in the rave scene.

Cass Pennant was a leader of the notorious West Ham hooligan firm, the ICF.

I remember a lot of the West Ham lads would come up to me on a Saturday at football, you know, what's happening to all our leaders, what's all this, what's all this rave music, you know, are we gone soft, are we fighting or are we raving?

It was hilarious.

I mean, so many of the football boys out there lightened up an incredible amount, and I think that that's probably got to be down to something, maybe a little pill here or there.

The loved-up vibe generated by ecstasy was infectious, even for the most hardened hooligans.

It wasn't long before the firms were organising parties themselves.

I was employed as security, but there was only two of us.

I mean, it was so peaceful, these rapes.

I'll never forget, you know, the promoter come up and said, Cass, behave yourself.

I said, why is that?

He said, you've got some guests that you ain't going to like.

I said, who's that in?

He said, Millwall.

I said, that's not a problem.

You know what I mean?

I've seen everyone getting on.

You know what I mean?

No, he said, you ain't going to like this.

Yeah, there could be as many as 200 of them.

I said, what?

I said, you've employed two of us.

He said, well, there's been a few other teams as well, Chelsea, Arsenal, all mixed in.

He said, look, you've only got a problem because you're old guard, you're old school.

He said, you've got to get with it.

I absolutely played witness to seeing Millwall and Chelsea dancing together, hugging each other and talking to each other.

And they would normally obviously be killing each other, you know, after invading a pitch somewhere.

I couldn't believe the whole night, yeah, was just a great buzz.

You know, it's just one big loving.

It wasn't just football hooligans who were putting their differences aside.

That's the thing about the rave culture.

In ecstasy, it broke down barriers between people, cos in Thatcher's Britain, it was more like a divide-and-conquer kind of thing, and you're a scout and they hate you cos you're from Liverpool and you're cocky and wanky and that.

I think it was a revolution of the mind with people, and all those attitudes were brought down.

There was a coming together of classes.

You'd get Emma Ridley and girls like that, which were the it girls of the day.

You'd get football hooligans from West Ham supporters.

You'd get rude boys from Brixton.

You'd get black, white, rich, poor, everybody, everyone really coming together.

This spirit of togetherness had echoes of another loved-up era, the hippie movement and 1967's Summer of Love.

Some people kind of try and talk about 89 as, you know, the second summer of love, because there was a sense, like the hippies, that in 89 it wasn't about Labour or Tory, it was about this world or a different world.

Love, love, love, love Anyone could see that there was love

We are going to change the world.

We're going to make everyone happy people.

We're going to make everyone like us.

And that was new.

That was special.

We really thought we were starting a revolution.

But there was an irony at the heart of this idealistic youth movement.

By now, the rave scene was being run by businessmen.

On one hand, you've got a whole generation of people who wanted to escape this sort of Thatcherite rule.

and sort of Acid House was a big part of that.

On the other hand, you'd got people who were making the sort of money out of it who could have only been using the sort of enterprise that was set free in Thatcher's time as well.

Some of the biggest rave promoters had learned their trade organising a very different type of party.

The notorious gate-crasher balls in London catered for hormone-raging, alcohol-guzzling public school kids.

What have you been drinking?

Vodka, wine.

You name it, I've been drinking it.

The 19-year-old entrepreneur behind the gatecrashers was Jeremy Taylor.

By the summer of 89, Jeremy had got out of the ball business and turned his hand to raves.

I definitely felt I was one of Thatcher's children, absolutely.

With the balls and then the raves, I don't think I could possibly get out of that one.

The rave culture was very entrepreneurial, and they were kids who had got on their bikes, got on their mobile phones, and, you know, set up these parties.

They were Thatcher's children.

She has only herself to blame.

The parties may have been enterprising, but they were also illegal.

In 1989, obtaining a license for an all-night event was impossible, so avoiding the long arm of the law was paramount.

It was so important to keep the location secret because if it got out, you know, your party was off.

So we used to have several venues.

So we'd have, you know, a venue, a backup venue, and a backup venue again.

It really was the most closely kept secret since the Holy Grail.

Rave locations range from farmer's fields to aircraft hangars dotted across the home counties.

Now easily accessible courtesy of the newly completed M25 motorway around London.

To keep venues secret, organisers provided only a phone number for partygoers to call to get directions at an allotted time.

Going to a party was quite a journey, it was a magical mystery tour.

You'd have a ticket, it would have a 0898 number.

People would go to phone boxes, ring this number, stuff in however many pound coins you needed to actually get an answer, write down the location.

and head off.

You'd sort of see cars going from all directions, from the suburbs of London, hundreds of people dressed a little bit differently, maybe converging.

There'd be a car park where there'd be a sort of pre-party party, everyone going, do you know where it is?

There'd be like a convoy going around the M25.

You'd drive around and you'd look for lasers.

the laser light it was like close encounters so he was driving through some dark field in the middle of something then all of a sudden you just see a light and you'd follow the light before you knew it you had a hundred cars behind you and and you used to get to these parties and be about 100 people then you look around and it was like 10 000 people when they stumbled across a rave the rural police forces often took an indulgent approach towards these strange gatherings

I think we soon realised that they were no great threat to us in terms of overt violence.

But of course, they're young and they want to party.

When we stopped them on the motorways, they would get a portable radio out and they'd all dance around the car for half an hour, you know, to their hip music and all this kind of thing.

In the early stages the police had no idea and in fact in the very early days the police were quite happy to help park cars and I think they were quite happy that everything was all contained under one roof.

But while at first the police were happy to humour the mass gatherings of young people in Britain,

Elsewhere in the world, there were authorities less willing to tolerate youthful rebellion.

On the 4th of June, the Chinese government finally lost patience with the students who had been occupying Tiananmen Square for the past seven weeks, and ordered the army to open fire.

The lines of troops across the entrance to the square regrouped as the injured were raced away on any available transport.

Despite the horror of the killings, one abiding image seemed to capture the sense that the world was changing.

One small person was stopping a whole row of tanks in China and it really did feel like things were possible.

All sorts of amazing things were happening in the world.

You know, you'd see people in an Eastern Bloc country all gathering in a central square with candles, and then their government collapsing, and freedoms everywhere, you know, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, everything seemed to be suddenly this huge surge towards freedom.

And they're away.

But some things never change.

Britain remained a class-ridden society, and Royal Ascot was the parade ground for the privileged.

Ascot was still very much the province of the kind of private punter rather than a morass of corporate entertaining.

And so that was still pretty special to get into the royal enclosure, which that year was, if I remember rightly, all black and white.

I love these.

Black and white.

Very smart.

Again, you see more black and white.

That's a very smart suit.

It was black and white polka dots, black and white stripy hats, and still was a sort of massive dress code.

And it was still kind of Toff's day out.

But even the most exclusive institutions weren't immune to the forces of Thatcherism.

I want it all!

I want it all!

I want it all!

In 1989, the corporate hospitality industry was worth £500 million.

A passport to privilege could now be paid for.

Britain was getting a little bit more like America, where people were footloose and fancy-free, and where money could buy you position, money could buy you the things that you wanted.

One of the big things about the summer of 1989 and to do with, you know, new money is people always want to kind of get next to new money, do they not?

And, you know, corporate hospitality was the big thing, you know, treat your clients to a nice day out.

Endless, really mega corporate entertaining binges, and they jolly well were binges too.

And if money could buy you class, celebrity was becoming the new aristocracy.

The celebrity event of the summer of 89 was the wedding of Rolling Stone Bill Wyman to his 19-year-old bride, Mandy Smith.

The sex antics of Rockstar are meat and drink to pegs like the sun.

Bill Wyman's 53.

Mandy Smith's 19.

And they had known each other for a few years before, if you get my drift.

Not only it was that unutterable disgrace, right?

Even worse than that is that Mandy Smith's mother starts going out with Bill Wyman's son.

It was the original celebrity wedding.

Anyone who was anyone was there.

The wedding was fabulous.

Don't let's kid ourselves, you know.

I mean, we had a fantastic time.

Why can't you sit down and have a chat with the Rolling Stones, you know?

And everybody was there.

Everybody was there.

It was just a great atmosphere.

Lovely to be here, mate.

I couldn't resist this, Phil.

I couldn't resist this.

It was the first of those real celebrity weddings that sort of made it into every broadsheet, as well as the kind of, you know, the fan magazines.

It was extraordinary.

it was only right that celebrity worship would need its own bible hello magazine had just hit the newsstands and devoted 14 pages to the wedding photos when you look at the beckham wedding which happened what about five or six years later and then the jordan wedding which is the ultimate i mean you can't get any further than that the jordan and pete wedding the mandy and bill wedding was the first of those kind of great weddings and it was in a way the first wedding which should have happened in the next decade

One group seeking to avoid media exposure were the rave promoters.

But despite their best efforts, the scene was about to be blown wide open.

On the hottest night in June, an aircraft hangar in Berkshire was transformed into a wonderland of throbbing sound and state-of-the-art laser lighting.

Hidden among the 11,000 guests was a team of undercover reporters from The Sun.

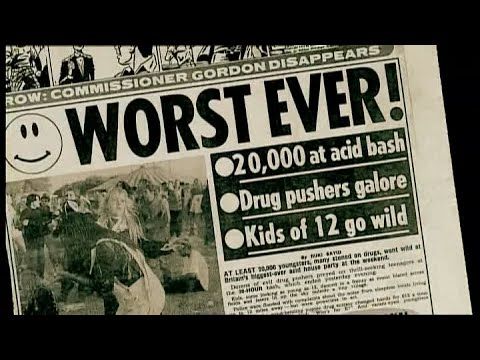

On Monday morning, the party was front-page news.

A friend of mine said to me, have you seen the papers today?

And I was like, well, what do you mean?

He said, go and buy the son.

And there was this, for the first time, the first time general public got to hear that this was going on.

It's a great story for tabloids for one important reason.

You could either read it as saying, cool, I wish I was there.

I'm going to go to the next one, right?

Or the older readers could say, bloody disgraceful, disgusting what's going on in our country, something must be done.

The Sun piece was full of outlandish details, including the claim that there were thousands of ecstasy rappers littering the floor of the hangar.

Actually, what that was, we had this really brilliant firework that went off and it showered everyone with these lovely silver, you know, bits of silver paper, so it looked like it was raining silver.

But anyway, that was the ecstasy wrappers on the floor.

Of course, there are some people who say that ecstasy doesn't turn up in wrappers.

Now, I'm slightly too old to know whether that's true or not.

All I can say is if the Sun said it was true in 1989, then it was definitely true, as we were selling 4.3 million copies per day, and we were the Bible of choice for young people.

Suddenly, Middle England was up in arms about this new disturbance of the peace.

Soon, questions were being asked in Parliament.

I remember a huge tabloid frenzy.

At the heart of the frenzy and the exaggeration was a real problem, which was really one of surprise.

People went to bed in some sleepy village.

There was a barn next door or an empty house.

And suddenly in the middle of the night there was this huge noise, cars, people shouting, music, loud music, drugs.

and something quite unexpected had hit them, and they were very frightened.

With raves, I suppose you, in one sense, you can say, well, this is a free society, very free.

But you might also argue it's freedom gone mad at midnight and after.

And that's really what people were complaining about, an abuse of freedom.

By now, the entire tabloid press wanted a slice of the story, and the rave scene was being branded as a serious threat to the authority of Mrs Thatcher's government.

In May, Mrs Thatcher seemed invincible.

By the end of July, everything seemed to be crumbling, especially the fact that she couldn't control her own country.

She talked a lot about the enemy within and about youth as a danger.

And here we were, running riot, the police trying everything they could to stop us, and nobody able to.

The police were no longer taking a lenient approach towards the raves.

They and the promoters became engaged in an increasingly elaborate game of cat and mouse.

It was almost like the competition, you know, we'd put on the party, they'd try and stop it, and it was, you know, it was the best man wins.

The organisers went to extraordinary lengths to throw the police off their trail.

We actually sent two decoy lorries out two hours in advance of the actual real sound systems in completely the wrong direction to where the party was happening, and it worked.

They were followed by the police, and they took them round the M25, and then after the police had gone, the two real lorries out the door to the venue.

Thank you very much.

We never knew where the parties would go and take place.

So we had to be as wise and adept as them at getting the manpower out.

So we worked on the principle that at any one time we could muster up to 300 to 400 police officers.

Now, the idea of that was if we could muster 400 police officers in the first hour, we could stop a party.

We had a copy at some point of the police manual which said, if there's 2,000 people in a warehouse, do not intervene because it will cause a riot.

So our objective was to get, you know, a full-figured number of people in there, get the party going, knowing that the police were just trying to prevent ravers getting through.

With the authority of the state seemingly under threat, the police started employing tactics that had last been used during the miners' strike.

that the rave promoters had done their homework and they had lawyers on hand to argue their case.

The police had blocked off the roads and they were not letting anyone through.

So everyone said, right, we'll park our car and we'll walk to the rave.

And the police were trying to stop them and our lawyer said, actually, you are not allowed to do that.

And they knew that he was right.

When roadblocks failed, the police tried a different tack.

They knew the promoters would be crippled without their communication network.

The police got clever and they started pressurising the phone companies and you'd see the phone companies would get their lines cut or suddenly become non-operational on a Saturday night.

And we'd have to use the pirate radio stations.

That's another Saturday night.

West Side People, yeah?

As we all know, the police are going to break in.

Pirate radio stations were now the only way to announce party venues.

The police decided two could play at that game.

We set up our own radio station to rival Sunrise, because Sunrise was one of the radio stations, and every time they would put out a message where the party was, and they'd do it in rap.

The party tonight is at Branzach, Kent, and the party tonight... And they'd roll on all the time like this.

And I used to get my youngsters to put the party tonight is at some hangar down in Essex.

Went wrong, went badly wrong for us because when they didn't find the party on one Saturday night, they looted all the garages down the A12 in Essex.

And the Chief Constable of Essex wasn't too pleased with Kent, that's for sure.

In July, the heat wave was showing no sign of letting up.

Another dry day, no end in sight yet to the drought-like conditions in the south.

Everywhere, clothes were being shed with abandon.

But soaring temperatures were no excuse for a drop in standards.

Harrods, the exclusive London store, wants it to remain that way.

And that's why it's banning shoppers it says are scruffily dressed.

Harrods wouldn't let people in shorts in.

which most people thought was amazingly stupid.

I mean, OK, maybe not barefoot, but sure, especially if you had good legs.

It was a very hot summer.

Generally, the zeitgeist was beginning to say, let it all hang out, you know, and so was the weather.

As the country basked in summer sunshine, Mrs Thatcher was feeling the heat too.

Inflation was on the rise, and the rash of one-day strikes had alarming echoes of the Britain of a more chaotic time.

the midst of this summer of discontent mrs thatcher announced the most radical cabinet reshuffle of her 10-year term she made 35 changes the most shocking of which was removing jeffrey howe from the foreign office for disagreeing with her over europe

the sacking, and it was a sacking, of Geoffrey Howe as Foreign Secretary, the man who'd been a right-hand man, in many ways the architect of the Thatcherite economic legacy.

When he and she could no longer look at each other, no longer speak to each other, that was a kind of turning point.

Mrs Thatcher began to say to me,

I can't rely on any of these people.

I'll have to do it myself.

Now, you may say that's egomania.

I think knowing her, it was despair.

There was a lot of despair about the way things were going.

And you could feel that authority was really draining out of it, that the life was draining out of the government.

With things going wrong at home, there was only one thing for it.

She went on holiday.

Mrs. Thatcher took a four-day break to Salzburg in Austria.

Talking about Mrs. Thatcher and holidays is somewhat incongruous because I don't think she liked holidays at all.

She felt they were an undue interference in the rhythm of life.

She wasn't a good holiday maker and she certainly wasn't the sort of person you would want to go on holiday with because she believed in working and her relaxation was to do a different kind of work.

She so loved what she was doing, being Prime Minister and handbagging people regularly.

But the idea of lying about like the Blairs do in somebody else's swimming pool simply wasn't on.

I can't imagine Mrs Thatcher anywhere near a swimming pool, actually.

While Mrs Thatcher was away, the mice were still at play.

Possibly sensing the end of an era, party organisers Sunrise planned the biggest outdoor rave yet.

Promoter Tony Colston Hayter paid a visit to a farmer who owned a large field near Longwick in Buckinghamshire.

We sat in the kitchen.

He opens his briefcase full of notes.

Well, I've never seen so many notes in my life, and to be honest, if you're in farming and you see that many notes all at once, it does happen to sort of sway you slightly.

But on the day of the party, things were suddenly hanging in the balance.

The police found out where the venue was and went and started, I don't know if they were intimidating the farmer, saying, you've got to call it off.

But we'd obviously had a contract with him.

I was in the position where if it went on, the council would probably take me to court.

If it didn't go on, Tony Colson, he would take me to court.

So I was a bit stuffed.

And really it was down to the farmer.

So it's, you know, whether he's going to be on our side or whether he's going to be on the side of the police.

And luckily he made the right decision.

The party went down in history.

Longwick was without doubt the biggest rave ever and the most unbelievable experience to DJ too.

We had fairground rides and we had the cups of tea being sold and we had the bouncy castles.

We had the best lights and we had the best sound system and we just had people as far as the eye could see smiling and having the absolute time of their life.

By daybreak, the party numbers had swelled to 20,000.

It was such a beautiful sight.

And it was like being in heaven, man.

The sun was just coming out.

It was a lovely, lovely morning.

That remains the best party of all time.

It was enormous, but even though it was so big, you had that feeling that you were part of something.

You weren't just a punter in a big crowd of people.

It was the way people were dancing.

Some of those people, there was one old boy on crutches.

He made a whale of a job of it.

There was another girl.

I'd never seen anybody dressed all in white.

Some of the sights and the people you see, they made you laugh just to look at them.

It was an eye opener for a country person to see all these people that come out of the town

and how they went on.

On Monday morning, Stuart McIntosh found himself with a field full of litter and some very irate neighbours.

I live four miles away and the sound was horrendous.

Just couldn't get away from it.

Shut the windows, you still heard it.

There was explosions and rattling all through the night and the music was thumping all through the night.

It was terrible.

The local people, they did take offence about it.

And if I ever went in the Red Lion, which is a very nice pub,

But they would all move up the other end.

So, you know, you didn't really bother going in there.

And people have never seemed to forget it.

But now looking back on it, I'm quite proud of what we did.

And it made a lot of people had a lovely weekend.

And I'll bet a lot of them still remember it to this day.

The carefree atmosphere of the summer was about to end.

In the early hours of Sunday, the 20th of August, a Thames pleasure cruiser, the Marchioness, was struck from behind by a river dredger and sank almost instantly.

The 132 young people on the boat were celebrating a friend's birthday.

Those who'd been on board were mostly in their 20s.

Even as they left hotels and hospitals where they'd been checked, many had no idea if friends had managed to escape.

I dived off and was taken by the tide and I allowed the tide to take me and it took me through and underneath and out the other side.

What happened to other people on the boat, did you know?

I didn't look back.

Marching this disaster was a seminal moment.

had a couple of close friends that passed away on that on that night probably knew about 50 people that were on the boat and in fact um could have been on the boat myself um as could jeremy there was one friend of mine who who'd survived from it and literally him and his two best mates had got onto the boat and they'd both jumped into the water when they when it went down

He survived.

The other two didn't.

So, you know, it was a very upsetting time.

With me now is the Transport Minister, Michael Portillo, who has spent much of the day at the scene of the tragedy.

Are you now going to tighten both safety and river traffic regulations?

Well, obviously, I'm very concerned to do so, if that is necessary.

I was Transport Minister at the time of the Marchioness, and my telephone rang, 5am, 6am, I don't remember, and I drove like fury towards the Thames, and there was nothing to see.

That's what struck me as so terrible.

You looked at the river and you knew many, many young people had died there in the night.

And there wasn't a scrap of wreckage, there wasn't a body, there was nothing.

It had all, of course, been washed away.

An emergency helpline was set up for concerned relatives.

In the confusion, many had no idea if their loved ones had survived.

I went into Canterbury Police Station and I went up to the desk and said, I want to find out where my son is.

I said, I know he was on the boat.

The gentleman came out in a uniform, took me up a flight of stairs into a room, started asking me lots of questions, how high he was and what colour eyes he had and everything.

i just you know police was asking questions so i just answering it and then the last question was what funeral director you're going to use and i just sat there and said you're telling me my son's dead and that's how i got to know sean i was on the missing list of presumed dead rather than focusing on the causes of the tragedy much of the media's reporting emphasized the privileged backgrounds of some of the victims

was portrayed in the media as if these were kind of rich kids running wild and it wasn't that at all this had nothing to do with drugs nothing to do with music it had to do with traffic on the thames and the way safety was run on the thames at the time 51 young people lost their lives and nobody really seemed to care and that was tragic autumn was on its way

The police were finally gaining the upper hand in their battle with the party promoters.

You got any raves on this weekend?

I'm coming up from Essex.

But it was raves' success that was its real undoing.

30,000 people, £20 a ticket.

You know, people were making a lot of money.

And where do you put all of that money?

I mean, you literally would see promoters and their staff running around with black sacks.

fibers there was cash everywhere i mean i remember going sort of into a porter cabin at one particular raid and there were people with nike sports bags just stuffing notes in and sort of walking off with it falling everywhere i mean the promoters too were completely off their heads so nothing was being counted properly or sorted properly with so much easy money around it was inevitable that the scene would attract some unsavory attention

We then had a load of people thinking, oh, great, I can go there and sell drugs or sell aspirins for 20 quid each, or, oh, if there's all that much money there, then I'll go and steal it from someone.

So it actually attracted the undesirables.

It was like the 30s in Chicago, you know?

Illegal alcohol was being brought in by the lorry load.

Dauben becomes stall pigeons for gangsters, yeah?

The drug scene really began to take a hold, because there was money there.

Public school boys Jeremy Taylor and Tintin Chambers began to realise they'd bitten off more than they could chew.

It's a very, very heavy London gang, came into our office.

you know, armed and said, give us half of your company or we'll kill you.

There were sort of middle-aged guys with big Macs on in the middle of August in the sweltering heat.

So we were pretty sure they were probably sort of tooled up underneath.

And they said, right, this party's not going ahead unless we get sorted out and left.

And I was like, well, you could have left a number.

Of course, our reaction to this was, well, who can we get in to protect us?

rather than, oh, my God, we're going to die.

I spoke to a family friend of mine who put me in contact with this SAS security firm where they're all either in the SAS or ex-SAS, and they came down to my flat and they looked around and said, right, OK, you need bars there, reinforced door here, and all the security was put in, and this guy is going to stay with you for however long you want him for.

I was very young and very naive and probably didn't realise what sort of situation we'd actually got ourselves into.

But being that young, you just had a lot of bravado and you just carried on.

It was just like, no, we're not going to let these people do this to us.

How dare they?

Go, go, go, go, go, go, go.

Go, let's go, go, go.

By now, the disreputable promoters far outnumbered the relatively responsible ones and the police were finding large quantities of drugs on their now regular raids.

There were so many really undesirable people around at the time and people pretending that it was a sunrise and making flyers up and it got harder and harder and harder.

And it was really towards the autumn and the winter, the net was closing in on us really.

The second summer of love may have been over, but some things would never be the same again.

If the start of the summer had seen the first fault lines appear in the old world order, the end of it would signal wholesale collapse.

Hungary opened its border to East German refugees and tens of thousands began to pour across in their Trabants to freedom in the West.

Finally, in mid-November, the Berlin Wall, the most powerful symbol of the East-West divide, was torn down.

It's the same image as Tenement Square, only this time the tanks didn't fire.

This time the East Germans pulled back.

And that was, of course, a huge change.

Unexpected, because when the same thing had happened before, in Hungary and the Czech Republic, and indeed in Berlin,

The tanks had fired and the young people had been killed.

This time, the young people won, and it was a very powerful set of images.

Back in Britain, there were other victories which, though less momentous, still seemed worth celebrating to the young people of the rave scene.

Black Box went to number one for six weeks without getting played on radio once, and all because it was being played at the raves that summer.

By the end of September, I think two-thirds of the charts were dance music.

Radio One had to start reassessing its playlists and adding this stuff.

Everything changed because of the raves.

And, as a sign of their arrival, the figureheads of the Manchester music scene, the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays, are invited to play on Top of the Pops on the same night.

I just remember actually going home at night to watch Top of the Pops, just because it was just such a special event.

I don't think there could have been a time when more people were celebrating their bands getting on Top of the Pops.

We hadn't bothered about whether any of those records were high in the charts or not, but suddenly they were.

There was a great feeling in Manchester that they were our bands.

They were representing a new kind of music.

That the summer of rave changed the face of British music is in no doubt.

But those at the heart of it would say its legacy went much further.

It changed the attitude of a generation.

It changed a lot of our thoughts and feelings about people.

And that's down to 89, man.

It's strictly down to them three months in 1989.

The end of football violence as we know it, in that form that used to shock the nation and shame the nation, that style of hooligan has gone forever on the back of the roof.

There is nothing like a youth culture exploding all around you, and to go in when it's at its absolute height, it was remarkable.

Well, I can tell you what I love telling my kids.

We don't follow fashion, we made it, mate, and that really does their heads in, you know what I mean?

That's the rhythm.

![[OC] How 🥼](https://videodownloadbot.com/images/video/e42/6gkk7tx9zyhq8qv391x3nelj5z7wy09t_medium.jpeg)